Given your background, why did you write an historical mystery and not a spy novel?

A life in intelligence work has taught me an important lesson: History matters. Life is sculpted from the raw materials of people, place, and time acted upon by the forces of personality, culture, and ideas. I enjoy looking back at crucial points in history to reexamine the interplay of these elements.

A good mystery is, of course, the best of all intellectual puzzles. So it seemed natural to try my hand at creating a new journey through an old time. I hope others will enjoy it, too.

Why Wyoming? Why 1870?

Wyoming in the 1870’s, to paraphrase Churchill on the Balkans, “manufactured more history than could be consumed locally.” In other words, a nearly isolated territory (not yet a state) of just 3,000 settlers (and many more Indians) became a crossroads to a new world. This territory welcomed thousands of settlers, miners, and soldiers who brought new wealth, new ideas, disease, hope, and violence to its land. Change triggered creativity as Wyoming passed the first law in the world allowing women to vote, elected the first woman justice of the peace, seated the first woman on a jury, and eventually elected America’s first woman governor and congressional representatives.

Major expeditions to Wyoming not only resulted in the world’s first national park, but also discovered the bulk of 19th century dinosaurs, sparking new interest in geology and paleontology. Competing dinosaur hunters actually buried or blew up their digs at end of each season in order to frustrate rivals. Salted gem mines, fatal blizzards, visits by Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister, travels by Russian Grand Duke Alexis guided by Buffalo Bill and George Custer, battles involving Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, and Sitting Bull, are all grist for the writer’s mill.

Why did you choose to write from the alternating perspectives of female and male protagonists?

I was inspired by the works of some of my favorite authors. After Tony Hillerman put Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee into the same novels, starting with Skinwalkers, I liked the way they pursued different lines of inquiry, but arrived at the same conclusion in the end. Although they often interacted, they didn’t always fully confide in each other. Margaret Coel expanded on this technique in her Wind River series, where two amateur sleuths from vastly different backgrounds—divorced Arapaho attorney Vicky Holden and recovering alcoholic Jesuit priest Father John O’Malley—look into crimes from their varying perspectives, don’t always reach the same conclusions and sometimes withhold information they believe could endanger the other, especially in Margaret’s most recent work, The Spider’s Web.

I wanted to use two diametrically opposed amateurs who are initially suspicious of each other’s motives and doubtful of each other’s abilities, but who nevertheless become bound by their fate. Between the lines, Murder for Greenhorns is a story of challenges faced by typical Americans in this period of postwar westward migration.

How did you come up with the names and characters of Kate Shaw and Monday Malone?

I decided on Kate’s name early on, inspired by the novelist Ian Fleming, who picked the blandest name he could from the author of a book on the birds of the Caribbean. That became the best known single-syllable character name in all of fiction: James Bond. My own family background is from New York and Pennsylvania, so I used Buffalo, NY as Kate’s home. Only after finishing the first draft of Greenhorns did I find out that the mother of the detective novel, Anna Katharine Green (The Leavenworth Case, 1878) grew up in Buffalo. In Greenhorns, Kate recalls advice from her friend Anna Green. Kate was also privileged to work on a newspaper partly owned by enterprising writer Samuel Clemens.

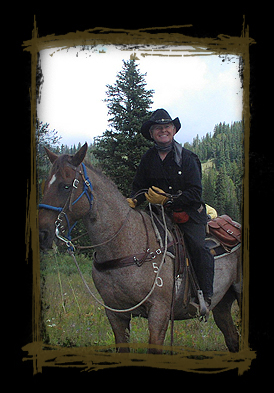

Growing up in the 1950’s, my heroes have always been cowboys. I wanted a poetic name for my Texas cowboy, so I created young Monday Malone. Monday has a rough background which is reflected by his name and which is typical of many of young men of this era. He is, I hope, a sympathetic personality who speaks to dilemmas of men even in our current era.

Is there a real Warbonnet?

On a map of modern Wyoming, you’ll find a small town halfway between Casper and Douglas, on the North Platte River and the Oregon Trail. The name of that real town is mentioned several times in Greenhorns when the boys play at their fort “up by the rock in the glen.” That town was founded a generation later than my fictional Warbonnet and I intend no resemblance to any of its citizens, living or dead. Don’t be fooled by the lines of a modern map. Wyoming counties changed boundaries many times and my Warbonnet really would have been in the earliest boundaries of Albany County, though it isn’t today.

Will there be more Monday and Kate adventures?

Let’s just say that Murder for Greenhorns is a mystery in all respects, including the future of the series. I can tell you that further Warbonnet mysteries are planned and they will feature appearances by many characters introduced in this first book. My hope is to portray what real life was like for the people of Wyoming in these turbulent and important times.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

I love reading about historical sleuths like Ellis Peters’ monk Brother Cadfael, Lindsey Davis’ ancient Roman PI Marcus Didius Falco, Elizabeth Peters’ Egyptologist Amelia Peabody, Kerry Fisher’s Australian flapper PI Phryne Fisher, and Clyde Linsley’s Josiah Beede. I enjoy works by Ann Parker and Steve Hockensmith set in the same time period that I explore.

I took great inspiration from the bodies of work by Tony Hillerman and Margaret Coel, as I said earlier, the unfailingly witty Wyoming mysteries of Craig Johnson, and the New Mexico mysteries of both Sandi Ault and Penny Rudolph.

I also read and enjoy some spy thrillers from authors like David Morrell, Gayle Lynds, Francine Mathews, and Charles McCarry (the American John Le Carre).

Is Murder for Greenhorns suitable for younger readers?

If Greenhorns was a movie, it’d probably be rated PG-13. When you’re considering nudity, violence, and profanity, there’s only a little of each. No sex takes places in the novel, but there are recollections of such experiences, without details. There’s a gunshot murder in chapter three and an ambush later in the book. The only other violence involves a shoot-out near the end. There’s no profanity in the book until Monday is driven to use it late in the story. Like most Westerners, he would never swear in the presence of a lady and he doesn’t do anything more than think an occasional “damn” until the climax. |