|

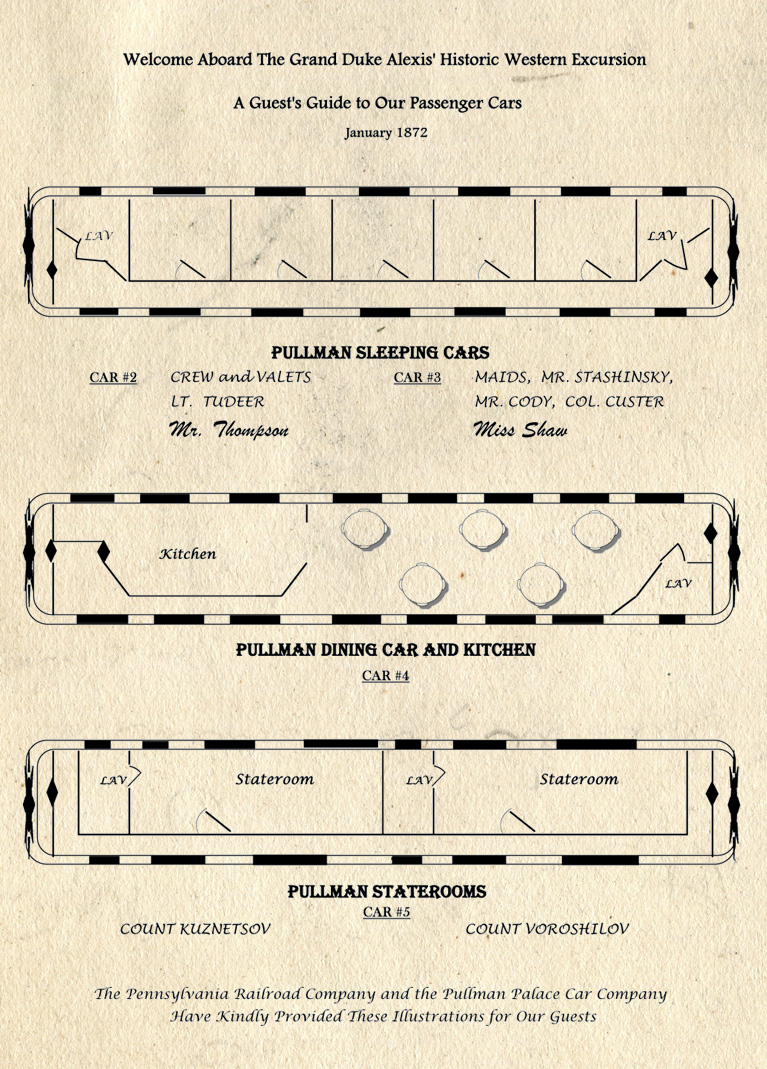

Prologue Two men sat in the darkest corner of the noisy Red Garter. From the way they watched the smoky room, their heads tilted somewhat toward each other, anyone would think the pair were plotting something. But there were so many plots in crowded, gold-rich Denver that they aroused no curiosity from the bartender, the staff, or the patrons. Hiding in plain sight, they were virtually invisible. The older and taller of the two poured a little more clear liquid into their shot glasses from a large pocket flask. He stoppered it and returned it to his coat. The younger man clinked glasses with him and they sipped in silence. “I have found,” the older man began in Russian, “that American women know nothing of vodka and can be had with just one drink.” He tasted his drink again and smoothed his mustache. The vodka was not quite cold enough, even though he had kept it in the outer pocket of his coat. “I don’t know if that is true,” his younger companion replied. “But it should be. American women can be had for two glasses of poor but overpriced champagne. They are not used to it and drink it like water. I’m sure they would treat this fine vodka the same way. Thank you for bringing it. Will the grand duke miss it from his stock?” He grinned with only one side of his mouth. The scar he concealed with a full brown beard made any facial expression slightly lopsided. The older man stroked his neat black beard briefly. “No, not likely. He and his guests consume so much, there was reason for concern that his supply would run out. Fortunately, when we were in Chicago, I ordered more to be sent up to us in St. Louis from the frigate in New Orleans. “But enough of vodka talk. And enough Russian. I know we could not be understood in here, but we will draw less attention if we speak English like everyone else.” “Maybe I can speak it like everyone else,” the younger one said, switching languages. “I learned American English from my time in California. Your accent and your more formal English would betray you as a foreign gentleman. We had best be brief.” He took out a small, leather-bound notebook and unfolded a hand-drawn map on their table. Even that would occasion no interest in the Red Garter. Maps to gold claims abounded in this city. Some of them were even fairly accurate, but rarely would a map lead to real gold. Lucky prospectors didn’t commit that sort of information to paper. But confidence men and swindlers did. “The weather is playing to our advantage, Dmitri Yurievitch,” the older man said, looking at the map. There was no writing on it, either in Russian or in English. “Great storms have passed over where we held our Nebraska buffalo hunt and covered the rail lines there and through Kansas in two meters of snow.” “Deeper in many places,” Dmitri said, tapping the eastern edge of his map. “I, too, have heard the tales of your returned train crew and passengers. The wind and snow continue to blow. These Siberian conditions mean the grand duke and his party could be stranded here for a week or more.” He grinned again and pointed out landmarks on the map to his companion—Julesburg, Cheyenne, and Laramie—all linked by rails. “And the route north from here, to Julesburg and Cheyenne, what of it? Is it, uh, blocked now?” “Parts of it, yes. The last train from Julesburg reported heavy snow to the east, in Nebraska. But the route west from Cheyenne through Laramie to Fort Bridger,” he traced the rail line west with his finger, “is said to be open, but there is much snow in the Laramie Mountains now.” “Denver is so crowded,” the older man lamented. “And the grand duke’s current American coterie is so large, it is almost impossible to set up a situation in which our hosts could be blamed for his death. If we could isolate him with a smaller party, we might be able to, to accomplish our task.” He grinned at the younger man and poured himself more vodka. Dmitri held his glass out for more. “You did well,” he said, “to plant the suggestion with the grand duke in Chicago last month that he should come west for a buffalo hunt. And General Sheridan was so willing to please. What a shame you could not find a way last week.” “Ah, well, that opportunity failed to live up to my hopes. We had many red Indians with us, two troops of cavalry, most male members of the delegations of both countries, even a military band, if you can imagine. They played in the snow, losing pieces of lip on their mouthpieces, the spit freezing in their instruments. There was perhaps a single opportunity when the grand duke was out front with Custer, but my horse could not keep up. And after that,” he shrugged, “no one was allowed to carry a loaded weapon into camp. We had to fire off every shot as we rode gallantly back from the big slaughter.” He swirled his glass and continued. “I tell you, Dmitri, I was hoping to bury what they call a tomahawk in the grand duke’s skull that night, but Custer slept in the royal tent. They both enjoyed the favors of the great chief’s daughter. Spotted Tail.” He laughed suddenly. “The father. That was the father’s name. Her name was Light Snow. Ironic. I think that is the word. I was confounded last week because of light snow. How can heavy snow and the rail conditions give us another opportunity?” “They both help and complicate matters. You said Sheridan’s back has been bothering him ever since I derailed his car and the grand duke’s three days ago in Cheyenne. The damage to Sheridan’s car cannot be fixed here in Denver, but there is a major rail yard.” He tapped the map. “Here, west of Cheyenne, in Laramie.” Dmitri went on. “If you were to put it into Sheridan’s head or the grand duke’s that the party might sightsee farther to the west, perhaps here, to Fort Bridger, they could leave Sheridan’s car at the Laramie yards for repair and go on to the pass near the fort. It would be fitting for the grand duke, probably a future admiral of the Imperial Navy, to say he stood where the waters flow to the Pacific, the Czar’s ‘eastern lake,’ as he has called it.” “That idea has merit, Dmitri. But why wouldn’t the party just stay in Cheyenne while the rail car is sent on to the Laramie yards?” “The whole party cannot stay in Cheyenne; they are too many. Besides, after a great snow last month near Julesburg, the railroad hotel in Cheyenne burned to the ground. There would be no suitable accommodations for the royal party and its large entourage.” “Hmmm. I see. Then the party—or a smaller group—would go west to Laramie and farther for a few days. I like it. Did you have anything to do with the hotel fire?” Dmitri folded up the map and put it and the brown leather notebook into his coat. “Yes, curious how fire has played such a role in bringing us a new opportunity. The grand duke wished to see the ruins of the great fire in Chicago. Sheridan came to see him there and the party stayed a week. That gave me the chance to plant the seed of the hunting idea. Now the burned hotel in Cheyenne provides us another stepping stone.” Dmitri finished his vodka. “I wish fire had worked to my advantage when I killed Stavrov in Laramie last month. He recognized me from our time together in California and I could not take the chance he might tell the American authorities—or the Secret Police agent in the grand duke’s party. I ought to have burned his body, or at least searched it. But I was in a hurry.” “Don’t worry about the Americans or the grand duke’s security, Dmitri,” the older man said, rising. “They likely haven’t thought to scout that far west for hazards. The Secret Police agent has had his hands are full worrying about the threat from red Indians. This is a violent country. I’m sure Stavrov’s death will go unnoticed. You did the right thing,” he said as the younger man put on his hat and scarf. “Do not hesitate to take such measures again.” They didn’t leave together. The older man sipped his vodka and assessed the charms of some of the women in the room. After failures in New York and Chicago, perhaps the empty, lonely Wild West would be the ideal place to kill the grand duke.

Chapter One Kate Shaw stood on the front porch of Martha Haskell’s boarding house savoring the very taste of the crisp, clean air. The dry snow sparkled in the noonday sun like millions of diamonds. Her breath came out in long, steady plumes. This was when Wyoming most reminded her of her home town, Buffalo, New York. She’d dressed in her best holiday frock, an ivory lace dress with puffed shoulders and a burgundy sash at her waist. She wore her long blond hair pulled back and pinned up over her ears. Monday Malone said that was his favorite hair style. Despite the chill on the porch, she wore only a light black lace mantilla as a wrap. Monday had given it to her last Christmas and she wore it to the church dances each month, as often as the fickle Wyoming weather allowed. The snow encircled the little town of Warbonnet like a fur ruff on a warm hood. It had drifted deep around the borders of the village in several snowfalls. But foot and animal traffic on the streets had stamped and melted it into frozen brown muck, treacherous for man and beast alike. Only the walks in front of each building and the duckboards between were safe to walk on. At last, she saw Monday coming up the boards from the marshal’s office. He crunched carefully over the ruts, gingerly maneuvering a flat wooden box he carried. It looked like it could carry a large picture frame. What could that be? Monday had brought presents for Martha and the children earlier in the week and hidden them in Kate’s room, with her help. Monday would make the holiday gathering complete. Livery owner Joe Fitch and blacksmith Bull Devoe had arrived a half hour ago. Bull corralled Buxton and Sally in his huge black arms while Joe put presents around the stove in the parlor. Kate and Martha had put up green boughs as decorations, but trees were too scarce out here on the windswept plains to cut even a little one for the house. Monday glanced up and saw Kate, but immediately looked down again to ensure his footing. What was he carrying that he was treating so delicately? At last he came up onto the steps, knocking the worst of the snow and muck from his boots. She ought to make him come inside in his stocking feet. She knew his socks were in good repair because she darned them herself. Her mother would be proud of her improving skill with needle and thread. But it was Christmas. She decided not to chide Monday on this day. He took off his boots without being asked. “Hello, Marshal. Merry Christmas. I thought you brought all the presents down here already.” “Morning, Miss Kate. And a happy Christmas to you, too. Uh, no. This here’s a special present that I couldn’t very well hide in your room. I was afraid I might slip bringing it here.” She reached up, took his hat from his sandy hair, and held the front door for him. After he set down the mysterious box, she helped him off with his threadbare hand-me-down coat. She grinned. In a little while, he’d have to find someone else to hand it down to. Martha had Christmas dinner laid out for them. Eleven-year-old Sally and her younger brother Buxton shared the far end of the table. Joe Fitch, who by the town council’s customary rotation would be the mayor starting in January, carved the ham. Kate smiled as Joe turned his head this way and that, his bushy black beard always pointed down at the meat he was cutting. Joe had dined with them frequently of late and Kate wondered if he wasn’t becoming a suitor of the Widow Haskell. When everyone had a full plate, Joe took up his water glass and proposed a toast. “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year for all those gathered under this roof.” Kate toasted the gallant citizens of Chicago and hoped they would find warmth and comfort in this cold season as they struggled to rebuild their city from last fall’s devastating fire. “Amen,” Monday offered, raising his glass. “And let’s all remember the fire that destroyed the Union Pacific Hotel in Cheyenne. May fires and other calamities give Warbonnet a wide berth in the coming year.” Bull snorted as he picked up a bite of ham on his fork. “You shoulda wished for no disasters for the next week, too. Year ain’t over yet.” Monday grinned but didn’t amend his wish. Dinner conversation turned to a favorite Wyoming topic: the recent weather. Widely spaced snowstorms had finally abated for the time being, allowing for some recovery in between. It had been three days since their last light dusting. Today was cold but clear. “Let’s hope the new year brings a successful conclusion to that Rooshan duke’s visit to America,” Martha said. The Laramie paper had been full of his doings in New York, Washington, Boston, and other eastern cities. He went to Canada for Christmas and was expected to re-enter the United States at Niagara Falls before touring cities in the Midwest. “I wonder if your family will see him in Buffalo, Kate,” Martha said. "Perhaps so. My mother knows how to meet royalty and she’d probably spend a week drilling social skills into my father and siblings if she thought there was the remotest chance of such a meeting.” As the adults laughed at that, Sally asked, “What special skills do you need, Miss Kate? Don’t you just shake hands with a duke, same as everybody else?” Kate chuckled. “I think gentlemen bow when they’re introduced and only shake hands if the duke offers his. We ladies should curtsy and offer a hand. He may take it or even”—she paused for effect—“kiss it. I understand European noblemen are great hand-kissers.” “Eewww,” Buxton said, shivering. “Kiss a girl’s hand? I’d never—” The laughter of all the adults stopped him cold. Monday caught his breath first. “You learn to start with just a hand, Buck. Then you work your way up from there.” He laughed again until he caught Kate and Martha’s disapproving looks. “Well, anyway, that’s what I’ve heard them princes do. In all the stories.” After they ate Martha’s pie, they adjourned to the parlor to open presents. Kate took Monday upstairs to help her bring things down. Highlights of the festivities included a lace mantilla from Monday for Martha this year, a new doll for Sally with hands and face carved by Bull and clothing made by her mother, and a small wheeled wooden horse Monday carved for Buxton. His mother approved of it more readily than the carved pistol Monday had given the boy last year. But the best gifts for the children were the ice skates Kate brought out. Hand-me-downs sent west by her parents from her brother and sister’s childhood, but enough to excite Sally and Buxton. Kate and Martha brought out their present for Monday, a red and black buffalo plaid blanket coat lined with sheepskin. Kate had learned a lot laboring alongside Martha sewing the sheepskin lining in before they assembled the coat. Monday was impressed when he tried it on. It was warm and fit him perfectly. “Why are you so surprised?” Kate teased. “I bring your laundry over here twice a week. It was easy to gauge your size.” She and Martha glanced at each other and shared a sigh of relief at the fit. “Oh, I almost forgot, please get your pistol belt. We had to guess how much of a slit to leave along the right side so you could wear your gun with this coat on.” Monday came back, buckling the belt. He put the coat back on and let his hand fall naturally. The side seam divided just above his holstered pistol. “Thanks, Miss Kate. And you, too, Martha. You keep giving me things that make my job easier. Pretty soon, I think either of you could be the marshal.” He grinned and removed the coat, then hung up his gunbelt again. Kate stroked her chin. “That’s not a bad idea, Monday. I wonder what effect female peace officers could have on law and order in this territory.” She didn’t smile. She wasn’t teasing him about this. Monday seemed to pale at the thought. Then he snapped his fingers. “I nearly forgot. I got that one special present left.” He picked up the flat box where it leaned against the wall and brought it over to Kate. It was heavy and looked impossible to open. Bull grinned at her; he must have been in on whatever this was. He brought out the tool he used to remove nails from horseshoes and deftly yanked out the nails so she could open the box. Inside, cushioned in straw, was a beautiful oval mirror in an ornate frame. “Oh, Monday, it’s lovely. It’s even nicer than my mother’s mirror. How did you get this up here from Laramie? Roy’s wagon bounces so.” “You recall that new mare I brought back last month? I outfitted her with a pack saddle and this was her only cargo. She was much more gentle than Roy’s wagon woulda been. I didn’t open it, but there was no sound of anything being broke. I know how you’ve wanted a bigger mirror than that little hand glass you have.” “It’s lovely. Thank you. Never mind a grand duke. I’ll feel like a princess when I use this. I’ll put it up over my bureau.” Monday marveled at the sheepskin-lined pockets in his coat as they went out onto the front porch. Kate hadn’t brought gloves, and was startled when Monday boldly took her left hand and placed it in his right coat pocket along with his own hand. As they walked toward the river, Kate thought this was one of her happiest Christmases, even if she was a long way from Buffalo. “You miss it, don’t you?” Monday asked, breaking into her thoughts. “Home, I mean.” “Frequently, but only a little on a day like today. I did a foolish thing last summer, when I contemplated leaving here and going back east.” She remembered Anton Schonborn and shivered at the memory of his hands on her, despite her warm coat. Word had come this fall that the Hayden expedition’s Yellowstone topographer had committed suicide, just days after the Chicago fire. He’d cut his own throat. She shivered again. “I’m glad now that I came to my senses in time. No, Buffalo isn’t home any more. Warbonnet is—” Her words were cut off by Buxton’s yell. They both looked up toward the nearby river. The boy ran toward them in stocking feet. “Miss Kate, Marshal! Sally broke through the ice! She’s—I gotta tell Ma!” He ran as if to pass them. Kate barely heard Monday say something to the boy as she sprinted the last few yards toward the riverbank, stripping off her heavy coat as she ran. She had time to see Sally desperately clinging to the edge of broken ice, with dark water churning around her. The girl was maybe twenty feet away and a little below the low bank. Kate made her decision, tilted her head down, and launched herself. She sailed off the low bank like a gliding bird and took the shore ice gently, spread flat on her stomach, sliding toward the frightened girl. But her momentum abandoned her two feet short of Sally. Desperately, she pushed with her feet and scrabbled with her fingernails. Just as Sally’s hand slipped from the edge, Kate seized her wrist. Kate heard Monday’s clumping boots almost on top of them. “No, no, stay back!” she shouted. “I’ve got her. Don’t come out here, Monday. The ice won’t take your weight.” “Now, Sally, everything will be all right,” Kate said, with a calmness that didn’t match how she felt. Could the girl hear Kate’s heart pounding against the ice? “Give me your other hand.” Kate ignored the intense cold coming up through her thin lace dress and camisole. She took Sally’s other hand, blue with the chill, in her own. “I’m going to pull you toward me, Sally. I want you to reach farther up my arms as I do. You’re going to have to climb along me. Use me like a ladder. Come on, now. That’s it. Never mind my hair, just pull yourself past me. Yes, yes, come on. My legs next. Now stay flat and crawl toward the bank. “Monday! Can you get her?” “Yeah. I got her. Don’t move, Kate.” She heard Bull arriving. No mistaking his footsteps. Now she had to see to herself. Kate tentatively gripped the edge of the ice—less than an inch thick here—and tried to push herself backwards, but a large chunk broke off with a snap and her left arm and face plunged into the icy water. She tried vainly to find purchase with her right hand, but there was nothing. The force of the water pushed her head under. She couldn’t breathe. Her feet must be in the air by now. Kate reckoned that she was going to die. How ironic that she’d thought of killing herself this way six winters ago, after Stuart’s death. She’d long since gotten over her anger at Stuart’s betrayal. She wanted to live! The Niagara River hadn’t claimed her, but now the North Platte would. Sudden pain rocked her. Her ankles slammed together and she was yanked unceremoniously backwards, her chin impacting the edge of the ice painfully. She left the water and was dragged swiftly over the ice, sputtering water through chattering teeth. Strong hands grasped her from what seemed all directions and lifted her. Her hair was in her eyes and she couldn’t see clearly, but she felt her coat being wrapped around her. Monday picked her up—where was Bull?—and ran with her back toward the boarding house. She tried to ask about Sally, but no words would come out. Her tongue wouldn’t respond and she saw with a start that her chin was bleeding all over her ivory dress. She felt so tired. She just wanted to go to sleep, so all this would fade away. A blast of warm air hit her as Monday carried her inside. Martha shouted from back in the kitchen and the marshal took Kate there, banging her head against the door jamb. The young lawman swore at himself. He set her down in a chair and put her feet into a big pot. Martha poured in warm water and Kate started at the sudden pain. She still couldn’t talk. Buxton came in on their heels. “Mr. Fitch is comin’ with Doc Gertz, Ma. He’ll know what to do. How’s Sally?” Kate could see the girl was laying in Martha’s hip bath, stripped to her shift. Martha poured more warm water gently over her. The girl gasped. So Sally would live. Kate smiled and drifted off. The kitchen door banged open. “She’s trying to go to sleep. Don’t let her do that,” Doc Gertz roared. Of course not. Kate knew that. Her father was a doctor. She’d helped him treat hypothermia and frostbite often enough. She tried to raise her head, but her chin seemed stuck to her dress. Strong hands began to strip her clothes from her. She tried to struggle, but she was too tired. Martha yelled, “That’s enough, you men! Pull blankets off the beds and bring them down here. I’ll wrap her in them. Thank God she’s going to be all right. She will be all right, won’t she, Doc?” “Probably. The rest of you clear out of here now. Martha and I will get Kate out of her wet things. Bring them blasted blankets. And be quick about it. Throw ’em in here and don’t look at her,” he called after Bull’s footsteps thumped up the stairs. In the sudden quiet, he mumbled, “Where’s my needle and thread? What happened to her chin?” The last thing Kate heard before she slipped away was Monday’s voice. “I reckon that was my doin’, Doc. I asked Buck to bring the lasso I gave him for his birthday. I roped Kate’s feet. Guess I dragged her out a mite too fast. She looks like I cut her throat. Will she be all right?”

Chapter Two Fresh snow meant few parishioners. An overnight storm had dumped enough new snow on Warbonnet that few nearby families had joined the townsfolk for church this morning. Once a month, the schoolhouse became a church for circuit riding preacher Jonah Barnes. “She’ll get over it, Monday,” Becky said. “Doc says he doesn’t think there’ll be a scar. She’s probably madder about not being able to talk or laugh or sing. Think what we’d all be feeling today if you hadn’t been so handy with that rope.” Monday sighed. Becky was right. But he was sorry Kate was so touchy since the accident. He’d been looking forward to escorting her and Martha on the big shopping trip down to Laramie next month while school was closed. Would she still go? Would she speak to him once Doc said she could? Everyone had been congratulating him and Bull on saving Kate, but they seemed to overlook the fact that Kate had been the real hero, risking her life to save Sally. There were so few people here today that the usual competition in bidding for box lunches was absent. Lieutenant Matt Beamish got Becky’s lunch for a dollar, an unheard-of bargain. Her brother Corey was out with the Arrow Ranch stock today and Monday was able to get Kate’s lunch for just a dollar, too. This was only the second time in eighteen months that he’d been the top bidder for her cooking. She brought it over to his bench and sat next to him, but without her usual smile. Those stitches must really aggravate her. The skin under her chin must be tight and made it hard to smile. Reverend Jonah Barnes sat on her other side. Maybe he could get a few words or a smile out of Kate. She had to take soup for her own meal. No chewing for her yet, Doc had said. Martha Haskell and Joe Fitch joined Doc on the bench opposite them. Kate scratched something quickly on the writing pad she’d been carrying and handed it to Jonah. “Yes,” the young preacher said, looking at the paper. “Becky did sing well today. I was closer to her than usual and heard her clearly.” He turned to Kate. “But we’ll all be glad when those stitches come out and we can hear you again. Sing as well as speak.” “And laugh and smile,” added Martha. “Not so fast,” Doc said. “She’s still got to take it easy once I get them stitches out. If she doesn’t want any scarring . . . .” He broke off as Kate touched the old jagged scar on the back of her left hand, then her ankle, then her left shoulder. Finally, she drew a line under her chin with a forefinger and shrugged her shoulders. She was counting her scars. What was one more, she implied. Everyone looked at their plates in silence. Monday had counted along with Kate. Her mysterious hand scar that she wouldn’t tell anyone about, the scarred ankles from knife wounds a year ago last summer, and the bear claw shoulder scratch last summer in Yellowstone. He was ashamed to have caused additional marring of her beauty. Maybe if there truly was no scar when the stitches came out . . . . Becky giggled and leaned against the young lieutenant, where they sat in relative isolation at the end of a bench two rows away. Monday heard Kate sigh beside him. Kate and Becky were best friends; even Becky’s yarn last summer that Monday had kissed her hadn’t made Kate mad at either of them. “I understand Becky’s been teaching you to shoot, Kate,” Jonah said. “Or she did in the fall when you two still rode every Saturday.” Kate shook her head a little and made a “C” with one hand. “Oh, Corey’s been teaching you. The rifle, or the pistol?” Kate pantomimed aiming a rifle. Monday imagined Corey’s arms around Kate as he taught her breath control and sight picture. Now it was his turn to sigh. Corey was handsome and heir to the biggest cattle ranch in these parts. Jonah shared Kate’s education and many of the same interests and they laughed a lot together when he came to town each month. How could a poor lawman with hardly any land compete for her hand with those two? Five hundred acres! Corey’s family had nearly three thousand acres this year and hoped to buy more. Kate devoted herself to her soup. “Hey, Doc,” the big black man said. “Will Miss Kate be able to sing as soon as you take the stitches out?” In the awkward silence that followed, Kate set down her bowl. She pointed at Monday and indicated she had heard him sing that morning. And made a bit of a strained face as if to tease him. She hastily scratched a note and passed it to him. “You told me you sang to an audience of thousands,” Monday read aloud. He looked at Kate and grinned as she held her nose to indicate what she thought of his singing. “I told you the truth. I did sing before thousands. Thousands of cows. They had no complaints.” As the other diners laughed, Kate furiously scribbled another note for him. Monday looked at the note as she wrote, “And what do cows know about music?” He passed her question to the other bench so they could read it. “Well, I reckon they don’t know nothing about violins or drums. But they sure know horns.” He said it with a straight face and provoked so much laughter that all heads turned toward their bench. Kate held her forehead and shook her head in mock disgust. “All she ever does at my jokes is groan,” Monday said. “My humor won’t tax her smilin’ muscles any. Reckon she can still go with us, Doc? Will Kate be ready to travel?” “Oh my, yes. Weather permitting, that is. After not being able to speak for quite a while, I imagine she’ll have lot to say to you on the way. You’ll be sorry you teased her.” Monday hadn’t dared to tease her at all before today. He’d been very careful not to say much to her, for fear she’d try to respond and pull her stitches. Now she wrote another short note, slowly this time. Jonah read it. “Oh, yes,” the preacher said. “You have to go pick up those other two McGuffey Readers from my little class in Laramie. I’d forgotten you’re up to twenty students here, Kate. You’ll need every copy.” Jonah had been teaching “soiled doves” to read down in Laramie for nearly a year now, one or two days a month. “My, isn’t it grand the way Warbonnet is growing,” Martha said, changing the subject. “Kate has a full classroom and now we have a hundred and eighty people who call Warbonnet home, didn’t you say, Joe?” Joe didn’t usually have much to say. Everyone knew why Martha tried to get him into conversations. “That’s so,” said the bearded livery owner. “Me and Bull got our hands full now. Might have to take on a stable boy to help us out with all that new stock.” He grinned at Martha. He meant a job for young Buxton. “Be even more work if we get that stage line through here in the spring,” Bull said. “Line manager said they want to use our place for the stock relief. Mean about twenty more mules.” “And perhaps a hotel, then, too,” Jonah offered. “Unless of course, they’ve asked you, Martha.” “No, indeed. I have enough to do with boarders and taking in washing. A hotel would be too much work for me. Maybe a restaurant some day, if Warbonnet gets big enough.” “I think it will grow larger sooner than you think,” Jonah went on. “As soon as spring comes and I get a fifth Sunday one month, I plan to use it to go to Denver and talk to the bishop. I’m going to try to convince him to let me become the pastor of the church you’ve all been saving for. Maybe by next year—” Everyone spoke at once, encouraging Jonah and asking questions. Even Kate tried to speak. Monday watched her chin and saw little drops of blood form on it. He reached over and patted her there with his napkin before the drops could fall onto her bodice.

Chapter Three Murder, Kate thought. Why did there have to be a murder? It had taken Monday away almost as soon as they arrived here and she hadn’t seen him all day. She swore to herself. This system of having lawmen in Albany County also serve as county deputy sheriffs was sometimes dangerous for Warbonnet’s marshal, and often meant extra work. Sheriff Boswell had no need to pick Monday’s brain over a weeks-old crime. Just because he’d solved a pair of homicides here in Laramie last summer didn’t make him Auguste Dupin! Kate stood in front of Ivinson’s store, her arms loaded with packages tied up in string. The shopping trip had been delayed for more than a week because of bad weather. And even then, there had been tense moments as the two wagons braved the pass below Warbonnet Peak. Joe’s lighter wagon, with Martha, Buxton, and the recovered Sally aboard, had had to pull the other wagon with Monday, Kate, and Roy Butcher, out of more than one mire. If it wasn’t deep snow, then it was deep mud caused by an untimely thaw. But the important thing was that they had made it. This would be the only freight run Roy could make in January and many people in Warbonnet had sent orders with them. That was why two wagons made the trip. She was relieved to be able to speak again, but a week after Doc took her stitches out, smiling still didn’t seem natural to her. The skin under her chin was stretched taut now. There was only a small line when Martha had held her hand glass for her to see. Maybe no one would notice, but she wished that skin would loosen up and let her smile. Finally. Here came Monday back from the sheriff’s office to help her with these packages. They had to stack all the purchases in the room at the Frontier Hotel where Kate, Martha, and Sally slept. The boxes and bags wouldn’t fit in the room Monday, Roy, Joe, and Buxton shared. More snow in Nebraska had stopped several eastbound trains on sidings here. Hotel rooms as well as storage space were scarce everywhere in Laramie right now. The freight warehouse at the station was full and they couldn’t just leave their purchases in the wagons behind Dillon’s livery. Monday took off his hat when he came up onto the duckboards in front of the store. He took her packages from her, but stopped short when he saw all the others—larger ones—piled up on the bench. “Are those yours, too?” He struggled to put his hat back on. “They’re ours. Ones we brought orders for.” Strange to hear her own voice so strained. “Well, looks like I’ll hafta make two trips. ’Less Buck or Joe are in there.” He nodded toward the store. “They just took a load over to the hotel. Let’s wait for them and then we can all go with the rest. It’s not too cold out here today. What did you learn about the killing? Surely, if the sheriff and his deputies haven’t solved it, there’s not much you can do, is there?” “This feller about forty-five years old got his throat cut down by the rail yard one night in December. No papers on him. No witnesses. Body found frozen the next morning. Couple a peculiar things about him, though. He had maybe a hundred dollars on him, so whoever killed him didn’t mean to rob him. That’s certain. Then,” Monday ticked off a second finger, “He wasn’t wearing fancy clothes, but he had a real fine watch on him. Had those little letters around the face, ’stead of numbers, you know?” “Yeah, well, the funny part was the name of the watchmaker. Nobody in town can read it. I mean, it uses regular letters and all, but in some foreign language, we figure. Not enough a’s and e’s, things like that, and some letters are turned backwards.” Kate frowned. “Finally,” Monday noted, ticking off a third finger, “Dutch van Orden asked around and nobody remembered seeing this feller in town. When Dutch took a drawing of the dead man around to the Hog Ranch, though, one of the girls, Jeanette, remembered him.” He stopped short, as if considering whether to continue. “Go ahead. I know what goes on at places like the Hog Ranch. Part of my Wyoming education last summer.” What a name for a den of iniquity, she thought. “Uh, well, this Jeanette said he paid real well, but spoke with an accent, like he wasn’t from around here. Had a way of saying ‘not yet, not yet,’ when he meant ‘no’.” “That would fit with his foreign watch, I suppose,” Kate prompted him. “Anyway, they buried this feller about a week ago—” Kate cut in. “Did they really say that or just that they put him into a coffin? At this season, there’s no digging in frozen earth. They must just have him in unheated storage someplace until March.” “Hmmm. They just said he went into a coffin, and I forgot about the ground being solid. This place sure ain’t like Texas in the winter.” “No, it’s more like Buffalo. Well, here come Buxton and Joe. We can talk more later. If you can find out where the corpse is stored, I’ll help you look at the body. Maybe we could learn something quickly to help Sheriff Boswell and then he’d let you alone for the rest of our visit here.” Monday looked at her funny. “That’s not so strange,” Kate said, trying to control her shivering. “I’m a doctor’s daughter. I’ve seen my share of dead bodies. Besides, this one’s frozen, isn’t he? I know I am.” # # #

There were no windows in the shed. Cal lit a lantern that hung by the door, then gave it to Kate. “You’re gonna need to be our lamp holder, Miss Shaw. Me and Monday will hafta move some coffins,” the deputy said. Kate shifted her sketch pad to her left hand so she could hold the lantern high. The shed looked half filled already, not a good sign, she decided. “Last year, we put the coffins on sawhorses,” Cal said, moving to a stack of boxes on the right side. “It was a peaceful winter. This year, there’s more folks dying of natural—and unnatural—causes.” The coffins were stacked in layers, with each succeeding layer turned ninety degrees. There must be thirty or more caskets. A significant number for a town of almost a thousand. Cal squinted to read pencil marks on some caskets. They’d been labeled on the foot end and on one long side. He tapped one foot end in the middle of a chest-high row. At least there were no coffins on top of it. He and Monday struggled to bring it down to ground level. Cal brought a nail puller from his belt and in another minute had levered off the lid. Kate brought the lantern closer. “Why are his eyes open?” “This is way we found him, Miss Shaw. Reckon he’d been dead a night and day by then. Damn cold that—’scuse me. I mean it was real cold that night. Too cold even for the coyotes who mighta found him first.” Kate nodded and leaned in for a closer look. “I thought maybe I could see the color of his eyes, but the ice prevents that. Perhaps if we’d thought to bring some water . . . .” She recoiled as Cal spat on one of the man’s eyes. It cleared for a moment. Black eyes. Then it glazed over again. “Well, that was certainly effective, Deputy. Thank you for helping me.” She looked up at the two men. Cal grinned. Kate noticed something else. Dried blood all down the front of the man’s shirt and coat. The wound wasn’t visible. She handed the lantern to Monday. “Hold it steady, please.” To Cal, she said, “I’m going to need some help here.” She began to work buttons loose so she could get a better look at the wound. When she couldn’t get a couple of buttons loose, Kate nodded to Cal. He pulled his belt knife and leaned in to snip away the fasteners. At last, the slashed throat was exposed. Kate had only seen one such wound before, helping her father back in Buffalo, but she wanted to appear professional. Kate measured the length of the cut with her fingers, then frowned. She pulled Monday’s hand with the lantern closer and peered at the wound. Then she raised her hand in a stabbing motion, twisting it one way and then the other. Finally, she reached down and put her hand into the frozen cut. Monday gasped and the lantern swayed. Shadows danced wildly. “Steady there,” Kate said. “I know what I’m doing.” There was no doubt about it. The wound was deeper on the right side of the man’s neck and tapered toward the left. If he had been stabbed from the rear, with the murderer reaching around his victim, then the killer was likely left-handed. Monday had solved a more difficult knifing by a right-handed killer last summer. “Kate,” Monday choked out. “Why did you put your hand into that cut?” “It’s all right, Monday,” she said, withdrawing her hand. She wished she’d thought to bring a handkerchief. The lantern made leaping shadows again as Monday removed his bandana with one hand. He passed it to her and she wiped her hand. “Thanks. I’ll wash up better when we get back. Whatever the truth of germ theory, the temperature in here should have killed those little bugs by now. He was cold as ice.” With that, she took out her sketch pad. “Deputy, would you hold the lantern now? I want to make a sketch of the victim.” Monday passed Cal the light with a look of grateful resignation. Kate positioned herself on one side of the body and began to draw.

|

© Copyright Robert Kresge, All Rights Reserved. Web Site design: www. blackegg.com |